Thank you for reading False Choices. This story received Top in Fiction Award! Enjoy!

The boys stood over the old wood tables, frantically folding papers and stuffing their bags.

“You can’t bring a bike into the station,” Mr. Margolis yelled. They all turned. There was a girl with a bike in the doorway. She hurried out and came back a moment later with her bag. Margolis handed here a bundle of papers and three extra. She put them all in her bag and dragged it to an open table. She watched the boy next to her fold the papers, and she copied him. She wasn’t a small girl, or a big girl, but her hands were small, he noticed.

“When the papers aren’t too thick, like today, you can do it like this,” offered the boy. He showed her how to fold one and get it tight, that it wouldn’t open when it hit the porch.

“What do’ya do when they’re thick?” asked the girl.

“Rubber bands work, or we just put them behind the door, or in the milk chute.”

The boys all folded their papers. Two boys were in a quarrel, fed by other boys, working it along to a fight, today or tomorrow.

One boy who had a small route was done and on his way, his bag filled. He grabbed one of the girl’s papers and tried to get away, but the boy stopped him with a hard shove.

“Don’t even try it,” exclaimed the boy. He dropped the paper and ran out, trying to make it look like he only wanted to harass her and not steal a paper. Margolis yelled at him as he turned out the door, “Why do you have to act like that?”

“He’s crazy today, been yelling non-stop,” his friend whispered to him.

He stopped folding papers and walked over to the desk. “I’m not going to deliver to the last house at Coplin and Hern anymore, 7272” said the boy.

“What, why not, he’s a customer, he’ll call in if he doesn’t get a paper?” demanded Margolis, standing up, straightening his glasses, peering at the boy, his shoulders forward, one hand on the desk, balancing his large frame.

“He came out naked yesterday like I told you, when I tried to put the paper in his door, he chased me across the street,” answered the boy, backing up a little, but not a lot.

The other boys started to laugh, someone threw some wadded up paper and it hit one of the florescent tube fixtures, which made it start to sway. The clamor rose, yelling at the boy, swearing at Margolis.

“You watch your mouth, you watch your mouth, I’ve never seen boys like you, such foul boys,” cried Margolis, lifting himself up on the toes of his large black shoes, finger pointing, his other hand swatting away a wad of paper.

The boy went back to his place and finished folding the papers. He took his canvas bag, gray with use and neglect, bulging with folded papers, and strode out the building. The girl followed him, dragging her bag on the floor. He sensed her behind him.

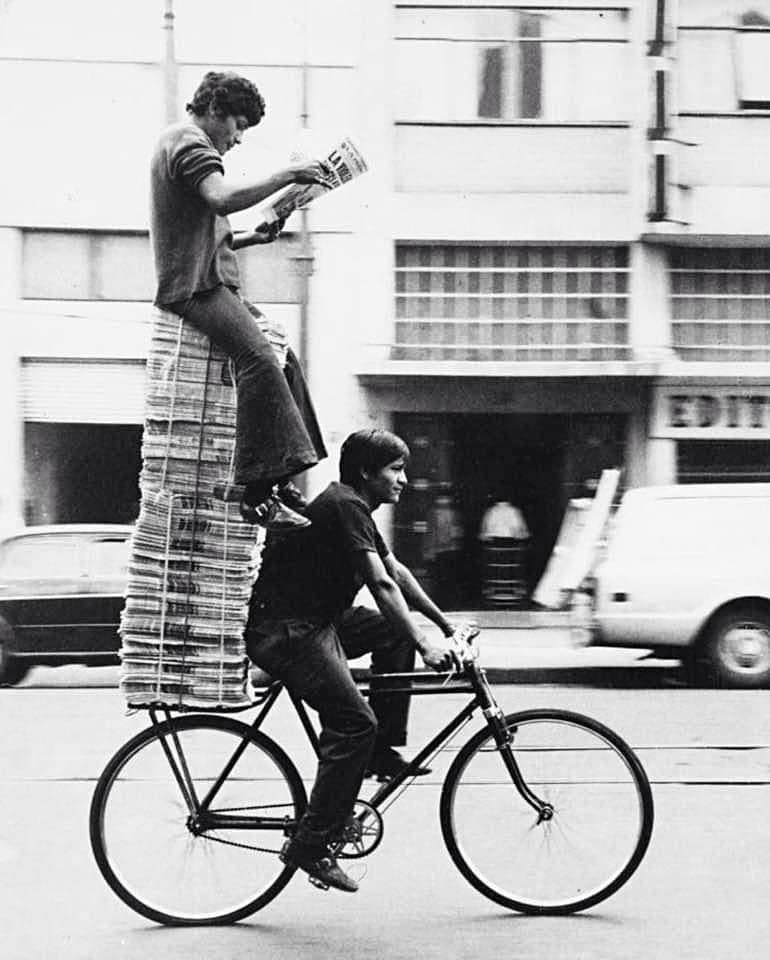

Outside, she tried to get the bag of folded papers onto her handlebars, but they swung around and she lost control. “Here, do it like this,” said the boy. Her walked her bike to the cement block wall of the station and leaned one handlebar and the back wheel against the wall. “Now hoist your papers, and rest them in the middle,” said the boy.

The girl took the bag and in one motion she lifted and dropped it between the handlebars, atop the bike’s fork.

“Now, go ahead and get on the bike, now,” said the boy. She threw her leg over the center bar. “Now, put the clips inside the handlebars.” It was the first time the clips had ever gotten shoved inside the plastic grips on the handlebars, so it took a little doing. He helped her push them in. “You’re good to roll.”

The girl leaned the bike away from the wall, straightened it out, and got one foot atop a peddle, then she shoved her other foot back while standing up on the pedal. He wasn’t sure it was going to work, but the bike wobbled forward and then she was peddling and the bike moved swiftly down the sidewalk and around the corner.

His friend came up and watched the launch. “Wow, she did it, wasn’t sure she was going to do it,” said the friend. “Yeah, me neither,” the boy said.

“What’s her name, what school she go to?”

“I don’t know either,” said the boy. He took care of his papers, lifting them up on the bike easily as he straddled the center bar, and situated them between the bars, steadying the bike between his legs without much effort. Margolis was behind him somewhere, yelling as usual. Margolis had come to the conclusion at some point that year that the more he yelled the fewer were the fights, the stealing, the chaos of the station. The boys came to hate his voice, so they got their papers and got out, talking amongst each other under the shouting. His was not the worst plan, and worked to some degree. The old man Margolis replaced was incapable of stopping the madness once it started, so the younger Margolis decided to prevent the problems from the get.

The boy rode his bike to Dickerson and Harper and crossed over the freeway there. There were men working on the golf course across the street, getting it ready for the season. He started to throw papers onto some of the porches, and for others he stopped, bounced up the stairs and left it between the doors, or in the milk chute. He delivered his papers, and came to the last houses at Coplin and Hern. A woman came to the door to take the paper. Her son used to deliver the route, so she was always nice to the boy. “That man had a visit from the police,” said the woman, with a slight smile, “hopefully he’ll calm down.”

The boy shook his head yes, handing over the paper. The woman stared at him now, and as he left, wondering what he thought of the man’s strange behavior, running around like that, screaming into the wind foul words that made no sense or sentences.

The days were longer now, it was still light out after the route was finished. The boy took his time pedaling home, exerting just enough to keep the bike rolling. He didn’t want to be home much before dinner, his Mom would find something for him to do; raking old, wet leaves from the fence line, cleaning the garage, picking up after the dog. The odd jobs never ended. He put his bike into the garage, and found the basketball. It was just warm enough out that he could handle the ball without frozen hands. The ball didn’t bounce a lot, but it was full of air. His hands felt a little raw against the smooth rubber. He played for an hour until his Dad came home. They walked into the house together, for dinner. The light was starting to falter now, almost seven.

II

Margolis watched for him, leaning back into the wooden desk chair, the yellow complaint in his hand, tapping, tapping against the papers on his desk. When the boy arrived, Margolis was ready, he lumbered into position, standing next to his desk, the complaint held high and started: “I told you he was going to call it in, and he did, he did, no paper delivered.”

“And no paper today, either. I’m not going back to that house, he’s a nut, coming after me like that,” replied the boy. He wouldn’t be bullied by Margolis.

“Ok, Ok, wuss, I’ll give the customer to her, she’s not a wuss, she’ll deliver it,” yelled Margolis.

The boy turned around. The girl was there, next to her spot on the table, cutting the wires on her bundle. “You know, he came after me naked,” warned the boy.

“He came after me naked,” copied Margolis, mocking. “You should have had a camera to take some pictures.” He laughed at his fine joke.

The girl didn’t say anything. Margolis handed the boy his papers. “Give one of those to her,” he said.

The boy handed a paper to the girl. “It’s another forty cents,” said the girl.

“Ok,” said the boy.

They folded and loaded, like everyday, and went out to deliver. From then on, the girl always got an extra paper, and the boy one less.

III

The weather warmed all week. Each day the girl came to the station and took her papers and didn’t talk to anyone. The boy looked at her, but she didn’t look back. When the sky clouded, rain not snow fell. On Saturday, the boy crossed the Coplin bridge early. There was little traffic on the freeway. On the other side of the bridge there was a large butcher shop, and there were always rats in amongst the cardboard boxes they left out. The boy avoided the boxes, not even looking at them. He got his papers at the station, a heavy load, and setup his bike, including saddle bags. The boy delivered the paper and the comics, the television guide and the circulars early. The sky had big white clouds that skidded along, and a cool breeze. Afterwards he got breakfast at home and then he collected his route. He rode his bike along the route and knocked or rang the bell for each customer. The sun was high and warm. He wanted to remove his jacket, but the wind was too chilly and his chest was wet. He had a wad of bills in his pocket now, and a lot of change. He ran into a group of kids from school, on their way to take the bus to Lansing for the high school’s championship game. The boy wanted to go, but the route held him back, he had to be up early tomorrow for the Sunday paper, and he had to collect today; the bill was due tomorrow, too.

On Sunday, the boy took his wagon to the station. The Sunday paper was too big and heavy for the bike, too difficult to balance. He ran most of the way, a jog really, but faster than a walk. He paid Margolis just what he owed, stuffed into a yellow envelope. Margolis didn’t say anything, just looked at the boy and then started to count the money. He loaded his papers into the wagon and got going.

It was a good day. The wind had settled and the sun would be up shortly. It was good to deliver on Sunday morning in the light. There had been rain overnight, and you could still smell it. The grass was greening, there were some small buds on the tree branches.

The boy finished his route, and it was still early. He found two more payments in milk chutes as usual. His bill paid, this was his money now. He kept up a light run and went over the bridge for the second time. He put his wagon within eye view of the counter at the Diner, went in and took his seat. There were lots of paperboys there. Fries and chocolate malts and little burgers with onions, called sliders. Across the street Margolis was smoking a cigarette outside the station, standing in the sun that had just peaked over the roof of the businesses that lined Harper Avenue. The boy had forgotten the championship game. He found a sports section and looked it up. They lost, 56 - 47. Not close enough. He cringed at the score. None of the other boys seemed to care.

Margolis was talking to a woman, who held her jacket tight against her. He kept shrugging his shoulder and holding the palms of his hands up. The boys lit cigarettes in the diner. End of the week smokes. A police car showed up in front of the station. “Hey, what the hell?” said one of the boys. They were all looking now. Margolis and the woman and the police officer were talking, and then the police officer helped the woman into the car and they rode off. Margolis went back into the office. The next day the paper carried a little story at the back of the front section about the paper girl who went to drop the paper behind the screen door of a house, and the owner, thinking it was the man he’d been fighting with all night, killed her with a single blast of his shotgun, right through the door. Alcohol was presumed involved, they noted, and Dad was sure of it. When the boy read it he saw that the house was on Lakeview, and not Coplin and Hern. They didn’t publish the girl’s name, or the mother’s name for that matter.

The boy remembered the girl and her small hands everyday when he picked up his papers, her place at the wooden table empty. “She should have never been a paperboy,” said his friend, and the boy agreed. No one mentioned her and what happened after a few days. Margolis did her route in his car. The boy wondered if he remembered to backtrack and deliver to the madman at Coplin and Hern.